Optimization Algorithms

In this chapter, we explore common deep learning optimization algorithms in depth. Almost all optimization problems arising in deep learning are nonconvex. Nonetheless, the design and analysis of algorithms in the context of convex problems have proven to be very instructive. It is for that reason that this chapter includes a primer on convex optimization and the proof for a very simple stochastic gradient descent algorithm on a convex objective function.

4.1 Goal of Optimization

Although optimization provides a way to minimize the loss function for deep learning, in essence, the goals of optimization and deep learning are fundamentally different.

- The former is primarily concerned with minimizing an objective.

- Whereas the latter is concerned with finding a suitable model, given a finite amount of data.

For instance, training error and generalization error generally differ: since the objective function of the optimization algorithm is usually a loss function based on the training dataset, the goal of optimization is to reduce the training error. However, the goal of deep learning (or more broadly, statistical inference) is to reduce the generalization error. To accomplish the latter we need to pay attention to overfitting in addition to using the optimization algorithm to reduce the training error.

To illustrate the aforementioned different goals, let’s consider the empirical risk and the risk. The empirical risk is an average loss on the training dataset while the risk is the expected loss on the entire population of data. Below we define two functions: the risk function $f$ and the empirical risk function $g$. Suppose that we have only a finite amount of training data. As a result, here $g$ is less smooth than $f$.

Figure to show the difference between the empirical loss which is based on the loss function defined by the data and the real risk.

4.1.1 Optimization Challenges in Deep Learning

We are going to focus specifically on the performance of optimization algorithms in minimizing the objective function, rather than a model’s generalization error. In deep learning, most objective functions are complicated and do not have analytical solutions. Instead, we must use numerical optimization algorithms. The optimization algorithms in this chapter all fall into this category.

There are many challenges in deep learning optimization. Some of the most vexing ones are local minima, saddle points, and vanishing gradients. Let’s have a look at them.

4.1.2.1. Local Minima

For any objective function $f(x)$ if the value of $f(x)$ at $x$ is smaller than the values of $f(x)$ at any other points in the vicinity of $x$, then $f(x)$ could be a local minimum. If the value of $f(x)$ at $x$ is the minimum of the objective function over the entire domain, then $f(x)$ is the global minimum.

For example, given the function

\[f(x) = x\dot cos(\pi x) \;\text{for}\;\; -1 \leq x \leq 2\]we can approximate the local minimum and global minimum of this function.

Illustration of the difference between global and local optimum.

The objective function of deep learning models usually has many local optima. When the numerical solution of an optimization problem is near the local optimum, the numerical solution obtained by the final iteration may only minimize the objective function locally, rather than globally, as the gradient of the objective function’s solutions approaches or becomes zero. Only some degree of noise might knock the parameter out of the local minimum. In fact, this is one of the beneficial properties of minibatch stochastic gradient descent where the natural variation of gradients over minibatches is able to dislodge the parameters from local minima.

4.1.2.2. Saddle Points

Besides local minima, saddle points are another reason for gradients to vanish. A saddle point is any location where all gradients of a function vanish but which is neither a global nor a local minimum. Consider the function $f(x) = x^3$. Its first and second derivative vanish for $x=0$.

Optimization might stall at this point, even though it is not a minimum.

Saddle points in higher dimensions are even more insidious, as the example below shows. Consider the function $f(x,y) = x^2 - y^2$. It has its saddle point at $(0,0)$. This is a maximum with respect to $y$ and a minimum with respect to $x$. Moreover, it looks like a saddle, which is where this mathematical property got its name.

4.1.2.3. Vanishing Gradients

Probably the most insidious problem to encounter is the vanishing gradient. For instance, assume that we want to minimize the function $f(x) = tanh(x)$ and we happen to get started at $x=4$. As we can see, the gradient of $f$ is close to nil. More specifically $f^{‘} = 1 - \text{tanh}^2(x)$ and thus $f^{‘}(4) = 0.0013$. Consequently, optimization will get stuck for a long time before we make progress. This turns out to be one of the reasons that training deep learning models was quite tricky prior to the introduction of the ReLU activation function.

4.2 Convexity

Convexity plays a vital role in the design of optimization algorithms. This is largely due to the fact that it is much easier to analyze and test algorithms in such a context. In other words, if the algorithm performs poorly even in the convex setting, typically we should not hope to see great results otherwise. Furthermore, even though the optimization problems in deep learning are generally nonconvex, they often exhibit some properties of convex ones near local minima. This can lead to exciting new optimization variants such as Izmailov et al., 2018

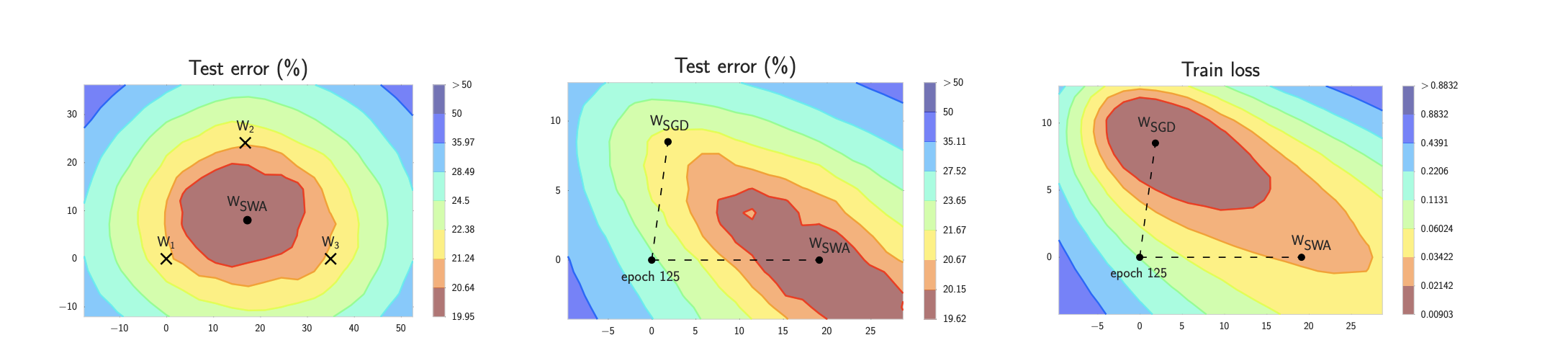

Illustrations of SWA and SGD with a Preactivation ResNet-164 on CIFAR-1001

. Left: test error surface for three FGE samples and the corresponding SWA solution (averaging in weight space). Middle and Right: test error and train loss surfaces showing the weights proposed by SGD (at convergence) and SWA, starting from the same initialization of SGD after 125 training epochs.

4.2.1. Definitions

Before convex analysis, we need to define convex sets and convex functions. They lead to mathematical tools that are commonly applied to machine learning.

4.2.1.1. Convex Sets

Sets are the basis of convexity. Simply put, a set $\mathcal{X}$ in a vector space is convex if for any $a, b \in \mathcal{X}$ the line segment connecting $a$ and $b$ is also in $\mathcal{X}$. In mathematical terms this means that for all $\lambda \in [0, 1]$ we have

\[\lambda a + (1-\lambda) b \in \mathcal{X} \textrm{ whenever } a, b \in \mathcal{X}.\]

This sounds a bit abstract. The first set is not convex since there exist line segments that are not contained in it. The other two sets suffer no such problem.

Definitions on their own are not particularly useful unless you can do something with them. In this case we can look at intersections. Assume that $\mathcal{X}$ and $\mathcal{Y}$ are convex sets. Then $\mathcal{X} \cap \mathcal{Y}$ is also convex. To see this, consider any $`a, b \in \mathcal{X} \cap \mathcal{Y}$. Since $\mathcal{X}$ and $\mathcal{Y}$ are convex, the line segments connecting $a$ and $b$ are contained in both $\mathcal{X}$ and $\mathcal{Y}$. Given that, they also need to be contained in $\mathcal{X} \cap \mathcal{Y}$, thus proving our theorem.

Illustration on how the intersection of two convex sets is also convex.

We can strengthen this result with little effort: given convex sets \(\mathcal{X}_i\) their intersection \(\cap_{i} \mathcal{X}_i\) is convex. To see that the converse is not true, consider two disjoint sets $\mathcal{X} \cap \mathcal{Y} = \emptyset$. Now pick $a \in \mathcal{X}$ and $b \in \mathcal{Y}$. The line segment in connecting $a$ and $b$ needs to contain some part that is neither in $\mathcal{X}$ nor in $\mathcal{Y}$, since we assumed that $\mathcal{X} \cap \mathcal{Y} = \emptyset$. Hence the line segment is not in $\mathcal{X} \cup \mathcal{Y}$ either, thus proving that in general unions of convex sets need not be convex.

Illustration on how the Union of two convex is not necessarly convex

Typically the problems in deep learning are defined on convex sets. For instance, $\mathbb{R}^d$, the set of $d$-dimensional vectors of real numbers, is a convex set (after all, the line between any two points in $\mathbb{R}^d$ remains in $\mathbb{R}^d$). In some cases we work with variables of bounded length, such as balls of radius $r$ as defined by

\[\{\mathbf{x} | \mathbf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^d \textrm{ and } \|\mathbf{x}\| \leq r\}\]4.2.1.1. Convex functions

Now that we have convex sets we can introduce convex functions $f$. Given a convex set $\mathcal{X}$, a function $f: \mathcal{X} \to \mathbb{R}$ is convex if for all $x, x’ \in \mathcal{X}$ and for all $\lambda \in [0, 1]$ we have

\[\lambda f(x) + (1-\lambda) f(x') \geq f(\lambda x + (1-\lambda) x').\]To illustrate this plot a few functions and check which ones satisfy the requirement. Below we define a few functions, both convex and nonconvex.

Example of convex and non convex functions

4.3. Gradient Descent

In this section we are going to introduce the basic concepts underlying gradient descent. Although it is rarely used directly in deep learning, an understanding of gradient descent is key to understanding stochastic gradient descent algorithms. For instance, the optimization problem might diverge due to an overly large learning rate. This phenomenon can already be seen in gradient descent. Likewise, preconditioning is a common technique in gradient descent and carries over to more advanced algorithms. Let’s start with a simple special case.

4.3.1. One-Dimensional Gradient Descent

Gradient descent in one dimension is an excellent example to explain why the gradient descent algorithm may reduce the value of the objective function. Consider some continuously differentiable real-valued function \(f: \mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\). Using a Taylor expansion we obtain

\[f(x + \epsilon) = f(x) + \epsilon f'(x) + \mathcal{O}(\epsilon^2).\]That is, in first-order approximation \(f(x+\epsilon)\) is given by the function value \(f(x)\) and the first derivative \(f'(x)\) at \(x\). It is not unreasonable to assume that for small \(\epsilon\) moving in the direction of the negative gradient will decrease \(f\). To keep things simple we pick a fixed step size \(\eta > 0\) and choose \(\epsilon = -\eta f'(x)\). Plugging this into the Taylor expansion above we get

\[f(x - \eta f'(x)) = f(x) - \eta f'^2(x) + \mathcal{O}(\eta^2 f'^2(x)).\]If the derivative \(f'(x) \neq 0\) does not vanish we make progress since \(\eta f'^2(x)>0\). Moreover, we can always choose \(\eta\) small enough for the higher-order terms to become irrelevant. Hence we arrive at

\[f(x - \eta f'(x)) \lessapprox f(x).\]This means that, if we use

\[x \leftarrow x - \eta f'(x)\]to iterate \(x\), the value of function \(f(x)\) might decline. Therefore, in gradient descent we first choose an initial value \(x\) and a constant \(\eta > 0\) and then use them to continuously iterate \(x\) until the stop condition is reached, for example, when the magnitude of the gradient \(|f'(x)|\) is small enough or the number of iterations has reached a certain value.

For simplicity we choose the objective function \(f(x)=x^2\) to illustrate how to implement gradient descent. Although we know that \(x=0\) is the solution to minimize \(f(x)\), we still use this simple function to observe how \(x\) changes.

Illustration of the process of convergence of gradient descent in a convex function.

12.3.1.1. Learning Rate

The learning rate \(\eta\) can be set by the algorithm designer. If we use a learning rate that is too small, it will cause \(x\) to update very slowly, requiring more iterations to get a better solution. To show what happens in such a case, consider the progress in the same optimization problem for \(\eta = 0.05\). As we can see, even after 10 steps we are still very far from the optimal solution.

the effect of choosing a small learning rate.

Conversely, if we use an excessively high learning rate, \(\left|\eta f'(x)\right|\) might be too large for the first-order Taylor expansion formula. That is, the term \(\mathcal{O}(\eta^2 f'^2(x))\) might become significant. In this case, we cannot guarantee that the iteration of \(x\) will be able to lower the value of \(f(x)\). For example, when we set the learning rate to \(\eta=1.1\), \(x\) overshoots the optimal solution \(x=0\) and gradually diverges.

The effect of choosing a large learning rate.

4.3.2. Multivariate Gradient Descent

Now that we have a better intuition of the univariate case, let’s consider the situation where \(\mathbf{x} = [x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_d]^\top\). That is, the objective function \(f: \mathbb{R}^d \to \mathbb{R}\) maps vectors into scalars. Correspondingly its gradient is multivariate, too. It is a vector consisting of \(d\) partial derivatives:

\[\nabla f(\mathbf{x}) = \bigg[\frac{\partial f(\mathbf{x})}{\partial x_1}, \frac{\partial f(\mathbf{x})}{\partial x_2}, \ldots, \frac{\partial f(\mathbf{x})}{\partial x_d}\bigg]^\top.\]Each partial derivative element \(\partial f(\mathbf{x})/\partial x_i\) in the gradient indicates the rate of change of \(f\) at \(\mathbf{x}\) with respect to the input \(x_i\). As before in the univariate case we can use the corresponding Taylor approximation for multivariate functions to get some idea of what we should do. In particular, we have that

\[f(\mathbf{x} + \boldsymbol{\epsilon}) = f(\mathbf{x}) + \mathbf{\boldsymbol{\epsilon}}^\top \nabla f(\mathbf{x}) + \mathcal{O}(\|\boldsymbol{\epsilon}\|^2).\]In other words, up to second-order terms in \(\boldsymbol{\epsilon}\) the direction of steepest descent is given by the negative gradient \(-\nabla f(\mathbf{x})\). Choosing a suitable learning rate \(\eta > 0\) yields the prototypical gradient descent algorithm:

\[\mathbf{x} \leftarrow \mathbf{x} - \eta \nabla f(\mathbf{x}).\]To see how the algorithm behaves in practice let’s construct an objective function \(f(\mathbf{x})=x_1^2+2x_2^2\) with a two-dimensional vector \(\mathbf{x} = [x_1, x_2]^\top\) as input and a scalar as output. The gradient is given by \(\nabla f(\mathbf{x}) = [2x_1, 4x_2]^\top\). We will observe the trajectory of \(\mathbf{x}\) by gradient descent from the initial position \([-5, -2]\).

To begin with, we need two more helper functions. The first uses an update function and applies it 20 times to the initial value. The second helper visualizes the trajectory of $\mathbf{x}$.

Gradient descent convergence in a 2d setting.

4.4. Stochastic Gradient Descent

In earlier chapters we kept using stochastic gradient descent in our training procedure, however, without explaining why it works. To shed some light on it, we just described the basic principles of gradient descent. In this section, we go on to discuss stochastic gradient descent in greater detail.

In deep learning, the objective function is usually the average of the loss functions for each example in the training dataset. Given a training dataset of \(n\) examples, we assume that \(f_i(\mathbf{x})\) is the loss function with respect to the training example of index \(i\), where \(\mathbf{x}\) is the parameter vector. Then we arrive at the objective function

\[f(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i = 1}^n f_i(\mathbf{x})\]The gradient of the objective function at \(\mathbf{x}\) is computed as

\[\nabla f(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i = 1}^n \nabla f_i(\mathbf{x}).\]If gradient descent is used, the computational cost for each independent variable iteration is \(\mathcal{O}(n)\), which grows linearly with \(n\). Therefore, when the training dataset is larger, the cost of gradient descent for each iteration will be higher.

Stochastic gradient descent (SGD) reduces computational cost at each iteration. At each iteration of stochastic gradient descent, we uniformly sample an index \(i\in\{1,\ldots, n\}\) for data examples at random, and compute the gradient \(\nabla f_i(\mathbf{x})\) to update \(\mathbf{x}\):

\[\mathbf{x} \leftarrow \mathbf{x} - \eta \nabla f_i(\mathbf{x}),\]where \(\eta\) is the learning rate. We can see that the computational cost for each iteration drops from \(\mathcal{O}(n)\) of the gradient descent to the constant \(\mathcal{O}(1)\). Moreover, we want to emphasize that the stochastic gradient \(\nabla f_i(\mathbf{x})\) is an unbiased estimate of the full gradient \(\nabla f(\mathbf{x})\) because

\[\mathbb{E}_i \nabla f_i(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i = 1}^n \nabla f_i(\mathbf{x}) = \nabla f(\mathbf{x}).\]This means that, on average, the stochastic gradient is a good estimate of the gradient.

Now, we will compare it with gradient descent by adding random noise with a mean of 0 and a variance of 1 to the gradient to simulate a stochastic gradient descent.

Stochastic gradient descent with a given noise. As we can see, the trajectory of the variables in the stochastic gradient descent is much more noisy than the one we observed in gradient descent. This is due to the stochastic nature of the gradient. That is, even when we arrive near the minimum, we are still subject to the uncertainty injected by the instantaneous gradient via

. Even after 50 steps the quality is still not so good. Even worse, it will not improve after additional steps (we encourage you to experiment with a larger number of steps to confirm this)

4.4.2. Dynamic Learning Rate

Replacing \(\eta\) with a time-dependent learning rate \(\eta(t)\) adds to the complexity of controlling convergence of an optimization algorithm. In particular, we need to figure out how rapidly \(\eta\) should decay. If it is too quick, we will stop optimizing prematurely. If we decrease it too slowly, we waste too much time on optimization. The following are a few basic strategies that are used in adjusting \(\eta\) over time (we will discuss more advanced strategies later):

\[\begin{aligned} \eta(t) & = \eta_i \textrm{ if } t_i \leq t \leq t_{i+1} && \textrm{piecewise constant} \\ \eta(t) & = \eta_0 \cdot e^{-\lambda t} && \textrm{exponential decay} \\ \eta(t) & = \eta_0 \cdot (\beta t + 1)^{-\alpha} && \textrm{polynomial decay} \end{aligned}\]In the first piecewise constant scenario we decrease the learning rate, e.g., whenever progress in optimization stalls. This is a common strategy for training deep networks. Alternatively we could decrease it much more aggressively by an exponential decay. Unfortunately this often leads to premature stopping before the algorithm has converged. A popular choice is polynomial decay with \(\alpha = 0.5\). In the case of convex optimization there are a number of proofs that show that this rate is well behaved.

Let’s see what the exponential decay looks like in practice.

As expected, the variance in the parameters is significantly reduced. However, this comes at the expense of failing to converge to the optimal solution. Even after 1000 iteration steps are we are still very far away from the optimal solution. Indeed, the algorithm fails to converge at all.

On the other hand, if we use a polynomial decay where the learning rate decays with the inverse square root of the number of steps, convergence gets better after only 50 steps

4.5. Minibatch Stochastic Gradient Descent

So far we encountered two extremes in the approach to gradient-based

learning: uses the full dataset to compute gradients

and to update parameters, one pass at a time. Conversely, (SGD) processes one training example at a time to make

progress. Either of them has its own drawbacks. Gradient descent is not

particularly data efficient whenever data is very similar. Stochastic

gradient descent is not particularly computationally efficient since

CPUs and GPUs cannot exploit the full power of vectorization. This

suggests that there might be something in between, and in fact, that is

what we have been using so far in the examples we discussed.

4.5.1 Minibatches

In the past we took it for granted that we would read minibatches of data rather than single observations to update parameters. We now give a brief justification for it. Processing single observations requires us to perform many single matrix-vector (or even vector-vector) multiplications, which is quite expensive and which incurs a significant overhead on behalf of the underlying deep learning framework. This applies both to evaluating a network when applied to data (often referred to as inference) and when computing gradients to update parameters. That is, this applies whenever we perform \(\mathbf{w} \leftarrow \mathbf{w} - \eta_t \mathbf{g}_t\) where

\[\mathbf{g}_t = \partial_{\mathbf{w}} f(\mathbf{x}_{t}, \mathbf{w})\]We can increase the computational efficiency of this operation by applying it to a minibatch of observations at a time. That is, we replace the gradient \(\mathbf{g}_t\) over a single observation by one over a small batch

\[\mathbf{g}_t = \partial_{\mathbf{w}} \frac{1}{|\mathcal{B}_t|} \sum_{i \in \mathcal{B}_t} f(\mathbf{x}_{i}, \mathbf{w})\]Let’s see what this does to the statistical properties of \(\mathbf{g}_t\) since both \(\mathbf{x}_t\) and also all elements of the minibatch \(\mathcal{B}_t\) are drawn uniformly at random from the training set, the expectation of the gradient remains unchanged. The variance, on the other hand, is reduced significantly. Since the minibatch gradient is composed of \(b \stackrel{\textrm{def}}{=} |\mathcal{B}_t|\) independent gradients which are being averaged, its standard deviation is reduced by a factor of \(b^{-\frac{1}{2}}\). This, by itself, is a good thing, since it means that the updates are more reliably aligned with the full gradient.

Naively this would indicate that choosing a large minibatch \(\mathcal{B}_t\) would be universally desirable. Alas, after some point, the additional reduction in standard deviation is minimal when compared to the linear increase in computational cost. In practice we pick a minibatch that is large enough to offer good computational efficiency while still fitting into the memory of a GPU.

comparison of the time of convergence between Gradient descent, stochastic gradient descent and batch gradient descent with two batches sizes.

4.6 Momentum

We reviewed what happens when performing stochastic gradient descent, i.e., when performing optimization where only a noisy variant of the gradient is available. In particular, we noticed that for noisy gradients we need to be extra cautious when it comes to choosing the learning rate in the face of noise. If we decrease it too rapidly, convergence stalls. If we are too lenient, we fail to converge to a good enough solution since noise keeps on driving us away from optimality.

4.6.1 Basics

In this section, we will explore more effective optimization algorithms, especially for certain types of optimization problems that are common in practice.

The minibatch stochastic gradient descent can be calculated by:

\[\mathbf{g}_{t, t-1} = \partial_{\mathbf{w}} \frac{1}{|\mathcal{B}_t|} \sum_{i \in \mathcal{B}_t} f(\mathbf{x}_{i}, \mathbf{w}_{t-1}) = \frac{1}{|\mathcal{B}_t|} \sum_{i \in \mathcal{B}_t} \mathbf{h}_{i, t-1}.\]To keep the notation simple, here we used

\(\mathbf{h}_{i, t-1} = \partial_{\mathbf{w}} f(\mathbf{x}_i, \mathbf{w}_{t-1})\) as the stochastic gradient descent for sample \(i\) using the weights updated at time \(t-1\). It would be nice if we could benefit from the effect of variance reduction even beyond averaging gradients on a minibatch. One option to accomplish this task is to replace the gradient computation by a leaky average.

\[\mathbf{v}_t = \beta \mathbf{v}_{t-1} + \mathbf{g}_{t, t-1}\]for some \(\beta \in (0, 1)\). This effectively replaces the instantaneous gradient by one that is been averaged over multiple past gradients. \(\mathbf{v}\) is called velocity. It accumulates past gradients similar to how a heavy ball rolling down the objective function landscape integrates over past forces. To see what is happening in more detail let’s expand \(\mathbf{v}_t\) recursively into

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{v}_t = \beta^2 \mathbf{v}_{t-2} + \beta \mathbf{g}_{t-1, t-2} + \mathbf{g}_{t, t-1} = \ldots, = \sum_{\tau = 0}^{t-1} \beta^{\tau} \mathbf{g}_{t-\tau, t-\tau-1}. \end{aligned}\]Large $\beta$ amounts to a long-range average, whereas small \(\beta\) amounts to only a slight correction relative to a gradient method. The new gradient replacement no longer points into the direction of steepest descent on a particular instance any longer but rather in the direction of a weighted average of past gradients. This allows us to realize most of the benefits of averaging over a batch without the cost of actually computing the gradients on it. We will revisit this averaging procedure in more detail later.

The above reasoning formed the basis for what is now known as accelerated gradient methods, such as gradients with momentum. They enjoy the additional benefit of being much more effective in cases where the optimization problem is ill-conditioned (i.e., where there are some directions where progress is much slower than in others, resembling a narrow canyon). Furthermore, they allow us to average over subsequent gradients to obtain more stable directions of descent. Indeed, the aspect of acceleration even for noise-free convex problems is one of the key reasons why momentum works and why it works so well.

As one would expect, due to its efficacy momentum is a well-studied subject in optimization for deep learning and beyond. See e.g., the beautiful How momentum works. For an in-depth analysis and interactive animation. Momentum in deep learning has been known to be beneficial for a long time. See e.g., the discussion by Sutskever.Martens.Dahl.ea.2013 for details.

4.6.2 The Momentum method

The momentum method allows us to solve the gradient descent problem described above. Looking at the optimization trace above we might intuit that averaging gradients over the past would work well. After all, in the \(x_1\) direction this will aggregate well-aligned gradients, thus increasing the distance we cover with every step. Conversely, in the \(x_2\) direction where gradients oscillate, an aggregate gradient will reduce step size due to oscillations that cancel each other out. Using \(\mathbf{v}_t\) instead of the gradient \(\mathbf{g}_t\) yields the following update equations:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{v}_t &\leftarrow \beta \mathbf{v}_{t-1} + \mathbf{g}_{t, t-1}, \\ \mathbf{x}_t &\leftarrow \mathbf{x}_{t-1} - \eta_t \mathbf{v}_t. \end{aligned}\]Note that for $\beta = 0$ we recover regular gradient descent. Before delving deeper into the mathematical properties let’s have a quick look at how the algorithm behaves in practice.

Convergence for the momentum method with learning rate 0.6 and beta 0.5.

As we can see, even with the same learning rate that we used before, momentum still converges well. Let’s see what happens when we decrease the momentum parameter. Halving $\beta=0.25$ it to leads to a trajectory that barely converges at all. Nonetheless, it is a lot better than without momentum (when the solution diverges)

Convergence for the momentum method with learning rate 0.6 and beta 0.25.

4.7. Adagrad

Let’ss begin by considering learning problems with features that occur infrequently.

4.7.1 Sparse Features and Learning Rates

Imagine that we are training a language model. To get good accuracy we typically want to decrease the learning rate as we keep on training, usually at a rate of \(\mathcal{O}(t^{-\frac{1}{2}})\) or slower. Now consider a model training on sparse features, i.e., features that occur only infrequently. This is common for natural language, e.g., it is a lot less likely that we will see the word preconditioning than learning. However, it is also common in other areas such as computational advertising and personalized collaborative filtering. After all, there are many things that are of interest only for a small number of people.

Parameters associated with infrequent features only receive meaningful updates whenever these features occur. Given a decreasing learning rate we might end up in a situation where the parameters for common features converge rather quickly to their optimal values, whereas for infrequent features we are still short of observing them sufficiently frequently before their optimal values can be determined. In other words, the learning rate either decreases too slowly for frequent features or too quickly for infrequent ones.

A possible hack to redress this issue would be to count the number of times we see a particular feature and to use this as a clock for adjusting learning rates. That is, rather than choosing a learning rate of the form \(\eta = \frac{\eta_0}{\sqrt{t + c}}\) we could use \(\eta_i = \frac{\eta_0}{\sqrt{s(i, t) + c}}\). Here \(s(i, t)\) counts the number of nonzeros for feature \(i\) that we have observed up to time \(t\). This is actually quite easy to implement at no meaningful overhead. However, it fails whenever we do not quite have sparsity but rather just data where the gradients are often very small and only rarely large. After all, it is unclear where one would draw the line between something that qualifies as an observed feature or not.

Adagrad by Duchi and al addresses this by replacing the rather crude counter \(s(i, t)\) by an aggregate of the squares of previously observed gradients. In particular, it uses \(s(i, t+1) = s(i, t) + \left(\partial_i f(\mathbf{x})\right)^2\) as a means to adjust the learning rate. This has two benefits: first, we no longer need to decide just when a gradient is large enough. Second, it scales automatically with the magnitude of the gradients. Coordinates that routinely correspond to large gradients are scaled down significantly, whereas others with small gradients receive a much more gentle treatment. In practice this leads to a very effective optimization procedure for computational advertising and related problems. But this hides some of the additional benefits inherent in Adagrad that are best understood in the context of preconditioning.

4.7.2 The Algorithm

Let’s formalize the discussion from above. We use the variable \(\mathbf{s}_t\) to accumulate past gradient variance as follows.

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{g}_t & = \partial_{\mathbf{w}} l(y_t, f(\mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{w})), \\ \mathbf{s}_t & = \mathbf{s}_{t-1} + \mathbf{g}_t^2, \\ \mathbf{w}_t & = \mathbf{w}_{t-1} - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{\mathbf{s}_t + \epsilon}} \cdot \mathbf{g}_t. \end{aligned}\]Here the operation are applied coordinate wise. That is, \(\mathbf{v}^2\) has entries \(v_i^2\). Likewise \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{v}}\) has entries \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{v_i}}\) and \(\mathbf{u} \cdot \mathbf{v}\) has entries \(u_i v_i\). As before \(\eta\) is the learning rate and \(\epsilon\) is an additive constant that ensures that we do not divide by \(0\). Last, we initialize \(\mathbf{s}_0 = \mathbf{0}\).

Just like in the case of momentum we need to keep track of an auxiliary variable, in this case to allow for an individual learning rate per coordinate. This does not increase the cost of Adagrad significantly relative to SGD, simply since the main cost is typically to compute \(l(y_t, f(\mathbf{x}_t, \mathbf{w}))\) and its derivative.

Note that accumulating squared gradients in \(\mathbf{s}_t\) means that \(\mathbf{s}_t\) grows essentially at linear rate (somewhat slower than linearly in practice, since the gradients initially diminish). This leads to an \(\mathcal{O}(t^{-\frac{1}{2}})\) learning rate, albeit adjusted on a per coordinate basis. For convex problems this is perfectly adequate. In deep learning, though, we might want to decrease the learning rate rather more slowly. This led to a number of Adagrad variants that we will discuss in the subsequent chapters. For now let’s see how it behaves in a quadratic convex problem. We use the same problem as before:

\[f(\mathbf{x}) = 0.1 x_1^2 + 2 x_2^2.\]We are going to implement Adagrad using the same learning rate previously, i.e., $\eta = 0.4$. As we can see, the iterative trajectory of the independent variable is smoother. However, due to the cumulative effect of $\boldsymbol{s}_t$, the learning rate continuously decays, so the independent variable does not move as much during later stages of iteration.

Adagrad convergence with a learning rate 0.6 and eta 0.4.

Now we will increase the learning rate to $2$ and we could much better behavior.

Adagrad convergence with a learning rate 2 and eta 0.4.

4.8 RMSProp

One of the key issues in Adagrad is that the learning rate decreases at a predefined schedule of effectively \(\mathcal{O}(t^{-\frac{1}{2}})\). While this is generally appropriate for convex problems, it might not be ideal for nonconvex ones, such as those encountered in deep learning. Yet, the coordinate-wise adaptivity of Adagrad is highly desirable as a preconditioner.

Tieleman.Hinton.2012 proposed the RMSProp algorithm as a simple fix to decouple rate scheduling from coordinate-adaptive learning rates. The issue is that Adagrad accumulates the squares of the gradient \(\mathbf{g}_t\) into a state vector \(\mathbf{s}_t = \mathbf{s}_{t-1} + \mathbf{g}_t^2\). As a result \(\mathbf{s}_t\) keeps on growing without bound due to the lack of normalization, essentially linearly as the algorithm converges.

One way of fixing this problem would be to use \(\mathbf{s}_t / t\). For reasonable distributions of \(\mathbf{g}_t\) this will converge. Unfortunately it might take a very long time until the limit behavior starts to matter since the procedure remembers the full trajectory of values. An alternative is to use a leaky average in the same way we used in the momentum method, i.e., \(\mathbf{s}_t \leftarrow \gamma \mathbf{s}_{t-1} + (1-\gamma) \mathbf{g}_t^2\) for some parameter \(\gamma > 0\). Keeping all other parts unchanged yields RMSProp.

4.8.1 The Algorithm

Let’s write out the equations in detail.

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{s}_t & \leftarrow \gamma \mathbf{s}_{t-1} + (1 - \gamma) \mathbf{g}_t^2, \\ \mathbf{x}_t & \leftarrow \mathbf{x}_{t-1} - \frac{\eta}{\sqrt{\mathbf{s}_t + \epsilon}} \odot \mathbf{g}_t. \end{aligned}\]The constant \(\epsilon > 0\) is typically set to \(10^{-6}\) to ensure that we do not suffer from division by zero or overly large step sizes. Given this expansion we are now free to control the learning rate \(\eta\) independently of the scaling that is applied on a per-coordinate basis. In terms of leaky averages we can apply the same reasoning as previously applied in the case of the momentum method. Expanding the definition of \(\mathbf{s}_t\) yields

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{s}_t & = (1 - \gamma) \mathbf{g}_t^2 + \gamma \mathbf{s}_{t-1} \\ & = (1 - \gamma) \left(\mathbf{g}_t^2 + \gamma \mathbf{g}_{t-1}^2 + \gamma^2 \mathbf{g}_{t-2} + \ldots, \right). \end{aligned}\]As before in Momentum, we use \(1 + \gamma + \gamma^2 + \ldots, = \frac{1}{1-\gamma}\). Hence the sum of weights is normalized to \(1\) with a half-life time of an observation of \(\gamma^{-1}\). Let’s visualize the weights for the past 40 time steps for various choices of \(\gamma\).

Weights decay for different values of gamma.

As before we use the quadratic function $f(x)= 0.1x_1^2 + 2 x_2^2$ to observe the trajectory of RMSProp. with a learning rate of 0.4, the variables moved only very slowly in the later stages of the algorithm since the learning rate decreased too quickly. Since $\eta$ is controlled separately this does not happen with RMSProp.

Convergence with RMSprop

4.9. Adam

So far we encountered a number of techniques for efficient optimization. Let’s recap them in detail here:

- We saw that is more effective than Gradient Descent when solving optimization problems, e.g., due to its inherent resilience to redundant data.

- We saw that batch gradient descent affords significant additional efficiency arising from vectorization, using larger sets of observations in one minibatch. This is the key to efficient multi-machine, multi-GPU and overall parallel processing.

-

Momentum added a mechanism for aggregating a history of past gradients to accelerate convergence.

- Adagrad used per-coordinate scaling to allow for a computationally efficient preconditioner.

- Rmsprop decoupled per-coordinate scaling from a learning rate adjustment.

Adam Kingma.Ba.2014 combines all these techniques into one efficient learning algorithm. As expected, this is an algorithm that has become rather popular as one of the more robust and effective optimization algorithms to use in deep learning. It is not without issues, though. In particular, Reddi.Kale.Kumar.2019 show that there are situations where Adam can diverge due to poor variance control. In a follow-up work Zaheer.Reddi.Sachan.ea.2018 proposed a hotfix to Adam, called Yogi which addresses these issues.

4.9.1 The Algorithm

One of the key components of Adam is that it uses exponential weighted moving averages (also known as leaky averaging) to obtain an estimate of both the momentum and also the second moment of the gradient. That is, it uses the state variables

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{v}_t & \leftarrow \beta_1 \mathbf{v}_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_1) \mathbf{g}_t, \\ \mathbf{s}_t & \leftarrow \beta_2 \mathbf{s}_{t-1} + (1 - \beta_2) \mathbf{g}_t^2. \end{aligned}\]Here \(\beta_1\) and \(\beta_2\) are nonnegative weighting parameters. Common choices for them are \(\beta_1 = 0.9\) and \(\beta_2 = 0.999\). That is, the variance estimate moves much more slowly than the momentum term. Note that if we initialize \(\mathbf{v}_0 = \mathbf{s}_0 = 0\) we have a significant amount of bias initially towards smaller values. This can be addressed by using the fact that \(\sum_{i=0}^{t-1} \beta^i = \frac{1 - \beta^t}{1 - \beta}\) to re-normalize terms. Correspondingly the normalized state variables are given by

\[\hat{\mathbf{v}}_t = \frac{\mathbf{v}_t}{1 - \beta_1^t} \textrm{ and } \hat{\mathbf{s}}_t = \frac{\mathbf{s}_t}{1 - \beta_2^t}.\]Armed with the proper estimates we can now write out the update equations. First, we rescale the gradient in a manner very much akin to that of RMSProp to obtain

\[\mathbf{g}_t' = \frac{\eta \hat{\mathbf{v}}_t}{\sqrt{\hat{\mathbf{s}}_t} + \epsilon}.\]Unlike RMSProp our update uses the momentum \(\hat{\mathbf{v}}_t\) rather than the gradient itself. Moreover, there is a slight cosmetic difference as the rescaling happens using \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{\hat{\mathbf{s}}_t} + \epsilon}\) instead of \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{\hat{\mathbf{s}}_t + \epsilon}}\). The former works arguably slightly better in practice, hence the deviation from RMSProp. Typically we pick \(\epsilon = 10^{-6}\) for a good trade-off between numerical stability and fidelity.

Now we have all the pieces in place to compute updates. This is slightly anticlimactic and we have a simple update of the form

\[\mathbf{x}_t \leftarrow \mathbf{x}_{t-1} - \mathbf{g}_t'.\]Reviewing the design of Adam its inspiration is clear. Momentum and scale are clearly visible in the state variables. Their rather peculiar definition forces us to debias terms (this could be fixed by a slightly different initialization and update condition). Second, the combination of both terms is pretty straightforward, given RMSProp. Last, the explicit learning rate \(\eta\) allows us to control the step length to address issues of convergence.

Convergence of the Adam method.

This conclude our lecture on optimisation. there still much to learn. For the interested reader try to read the Yogi method proposed to fix the Adam method.